Formation of the Hawaiian Islands

Hawaiian Islands Geology & Geography

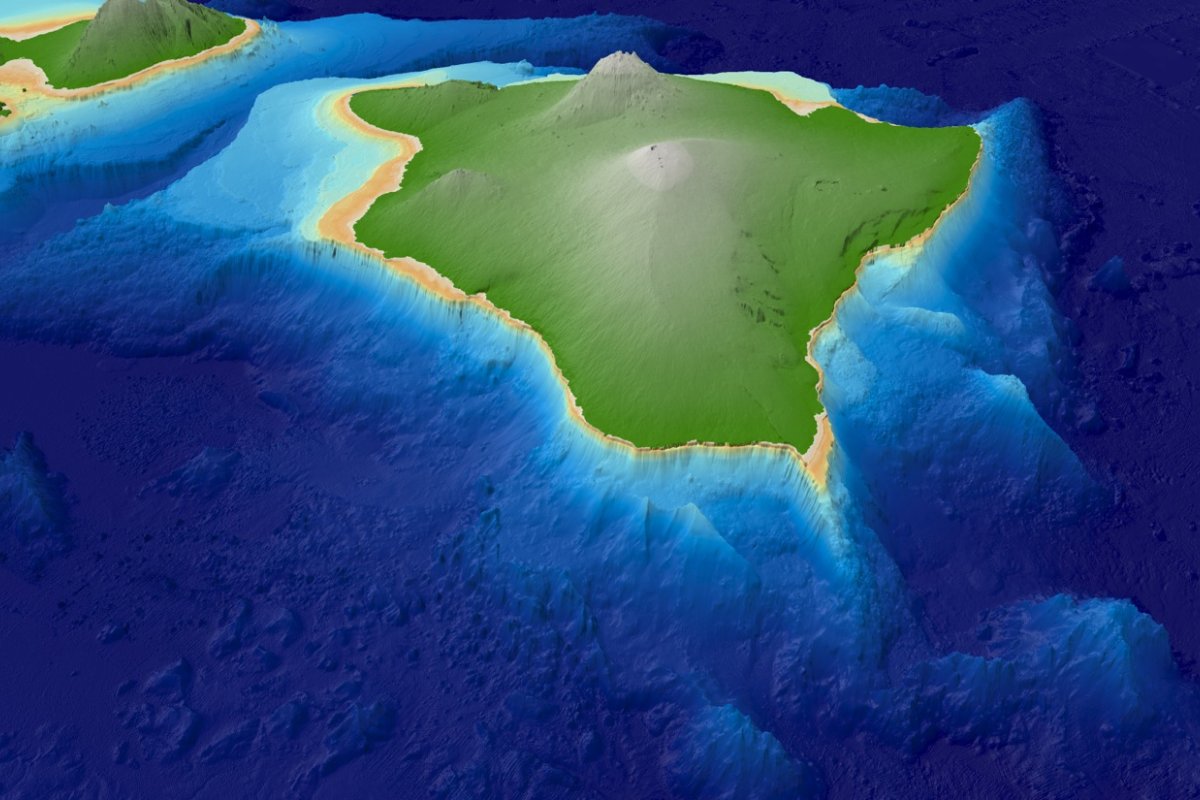

So you want to know what makes a Hawaiian island? Great, you're in the right place. While every island has its own story, and we'll touch on that, only one is a living example of a Hawaiian Island in the works - the Big Island. It's the perfect specimen to examine and use as an example. That said, let's take a look at the geology of the only islands you can still see physically growing by the day.

— article continued below —

2024 Hawaii Visitor Guides

Visiting Hawaii soon? Be sure to grab a copy of one of our updated Hawaii Visitor Guides.

~ Trusted by Millions of Hawaii Visitors Annually ~

The 'Hot Spot'

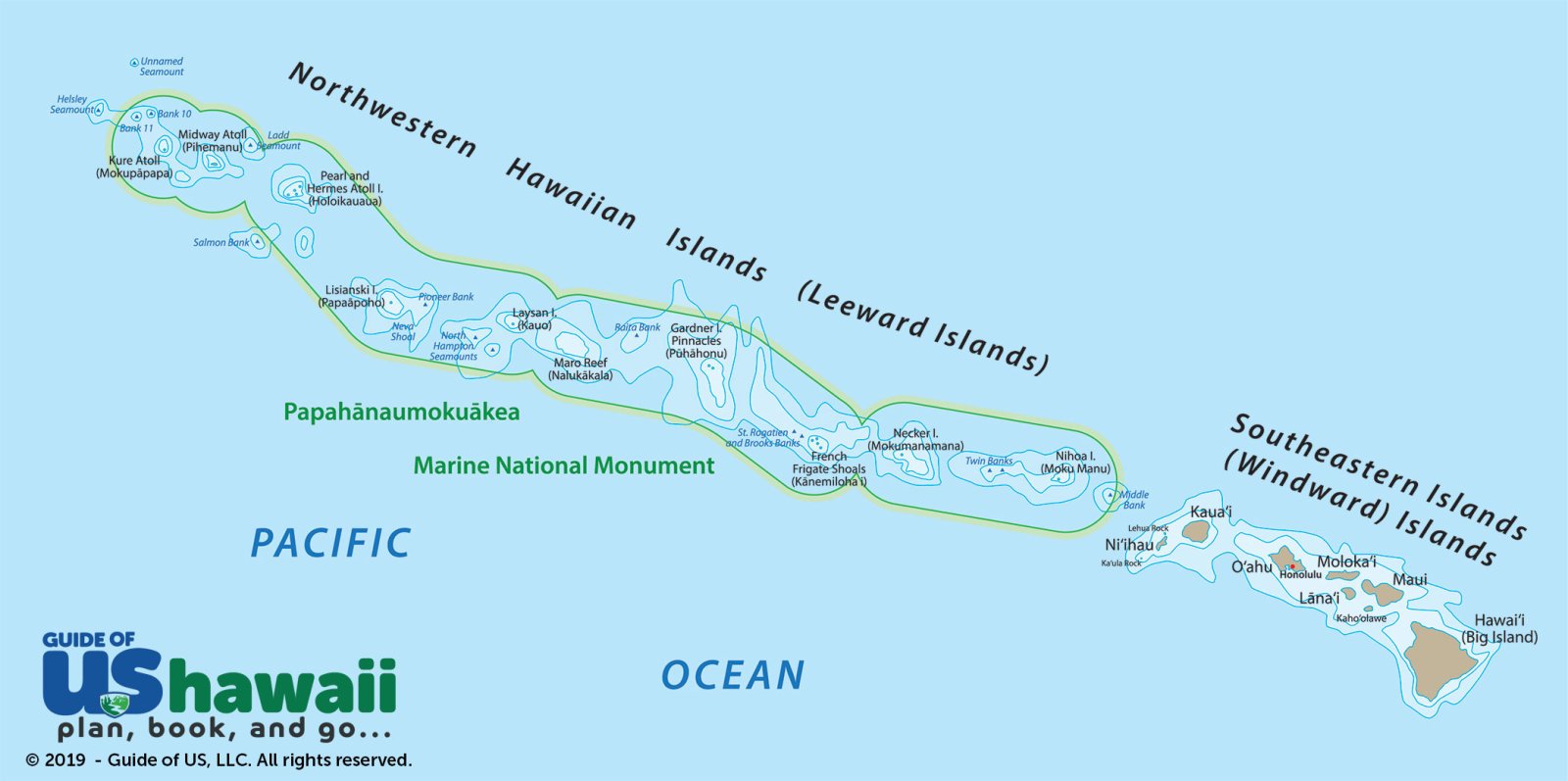

So what exactly is this 'hot spot' you hear so much about, and how does it form these beautiful islands? The answer to this question is fairly simple. The Hawaiian Islands are situated near the middle of the "Pacific Plate" on top of a 'hot spot.' This Pacific Plate is almost always moving northwestward at a rate of several centimeters per year, about the same rate as your fingernails grow. This constant northwestward movement of the Pacific Plate over a local volcanic "hot spot," or plume, has produced a series of islands, one after another in assembly-line fashion. The result is a chain of volcanic islands (Hawaiian archipelago, see above and links below) that consists of eight major islands and 124 islets stretching from the Big Island of Hawai'i along a northwest line for 1,500 miles toward Japan and the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. In total, the islands spread across an area of 6,459 square miles.

The Hawaiian Archipelago

The Big Island of Hawai'i is currently the largest landmass in the Hawaiian island chain. The eight major islands at the western end of the chain are, from west to east, Ni'ihau, Kaua'i, O`ahu, Moloka`i, Lana`i, Kaho`olawe, Maui, and the Big Island of Hawai`i.

Hawai'i, also the youngest island in this chain, began over a million years ago as five separate volcanoes on the ocean floor. As the five volcanoes erupted time and time again (not necessarily simultaneously but rather sequentially), they created thin new sheets of lava spread upon the old, building and building until the volcanic heads emerged from the sea. These mountains often would have flows that overlapped the other mountain's flows, and eventually, the five peaks would become the single island we see today (note the diagram on the next page). First, the Kohala Mountains formed as they sat over the 'hot spot' in the plate. But as the plate shifted, so did the location of the rising magma, moving to Mauna Kea, Hualalai, Mauna Loa, and eventually Kilauea. Even now there is a new seamount, named Lo'ihi, which is also forming off the southeast coast of the Big Island. In another 50,000 years or so, it too may become the next Hawaiian island, or it may even join to become the sixth peak of the Big Island. Currently, only the volcanic remnants of Kohala are completely extinct, never to erupt again. The rest of the volcanoes on the Big Island aren't quite done yet. Consider this a history lesson that's still evolving.

Big Island Land Area by Volcano

The Volcanoes of the Big Island

Mauna Loa, the Big Island's largest volcano makes up approximately 51% of the island, and most people still have a surprisingly hard time finding it when they are here. Mauna Loa means 'Long Mountain' and is given this name due to its large shield shape. This shape makes it difficult to distinguish Mauna Loa as an actual mountain.

The name 'shield volcano,' which is what all the islands in Hawai'i are, comes from a perceived resemblance to the shape of a warrior's shield. Molten lava rises from a hot spot in the earth's crust, erupts through various vents and rifts on the surface, and proceeds to move down the gentle slopes toward the ocean, building up layer upon layer over millions of years. Kilauea Volcano, the world's most active volcano and home to the fire-goddess, Pele, resides on the eastern slopes of Mauna Loa. At one time many believed Kilauea to be a vent of Mauna Loa, but today we know it has its own magma chamber and is completely separate from its larger cousin next door. Mauna Kea is the other major volcano on the island making up about 25% of the island's total landmass. Mauna Kea is significantly easier to spot than Mauna Loa, often recognized in winter months by its snowy cap, hence the name Mauna Kea - meaning 'White Mountain.' Reaching a total elevation of some 33,000 feet from the sea floor, of which only 13,780 (approx.) feet exist above sea level, the mountain is the highest point in the Pacific Ocean and the world's tallest mountain from base to summit.

The Big Island's other volcanic mountains are Hualalai in Kailua-Kona on the west side of the island and Kohala on the northwest tip of the island. Kohala is the oldest mountain on the island and shows much more geological wear than its younger counterparts. The amazing sea cliffs found in Kohala today were likely caused by a giant landslide some 200,000 years ago.

Mauna Kea and Hualalai are both considered dormant, like Haleakala on Mau'i. Chances are they will erupt again in the long-term future, though most likely to no significant degree (volume wise) as the hot spot no longer exists beneath them. Generally speaking, the only eruptions that occur beneath these dormant mountains are due to their subsidence into the ocean floor, usually a few thousand feet over time, which then heats and "pushes" any remaining magma up to the surface in the form of an eruption.

Unfortunately, while these eruptions lack volume, they can be somewhat violent and even explosive. Mauna Kea owes its steep slopes to an explosive type of eruption in the recent geologic past. Explosive eruptions often produce widespread ash deposits, which help build a steeper sided volcano like those found in the western United States. Today the physical differences between Mauna Kea (fairly steep sided due to 'recent' explosive eruptions) and Mauna Loa (still in its shield-forming stage) are very distinct. In its prime, Mauna Kea likely reached a few thousand feet higher than it does today. As previously noted, Mauna Kea remains the tallest mountain, from top to bottom, on the planet. From base to summit it towers some 33,000 feet. That's taller than Mount Everest. Plus if you consider what's subsided (sunk) into the ocean floor, which the USGS does take into account for mountain height, then the mountain is 56,000 feet tall. That's just incredible!

Mauna Loa and Kilauea are both considered active volcanoes. Before the most recent November 2022 eruption, Mauna Loa last erupted in 1984 and is likely to continue to erupt fairly significantly again in the near future. Since 1843, the beginning of well-documented historical data, Mauna Loa has erupted 34 times. Geologically speaking that makes it a very active volcano. Mauna Loa is by far the bulk (51%) of the Big Island and remains the world's largest (in mass) volcano. Normally, Kilauea makes all the news and steals the show, but Mauna Loa will also continue to remind us why it's the biggest volcano on the island. Mauna Loa can erupt significant amounts of lava in a very short time frame, dwarfing Kilauea.

Kilauea once believed to be merely a side satellite vent of Mauna Loa but now recognized as its own distinct volcano, is the world's most active volcano, erupting almost continuously since 1983. Between January 1983, and June 2007, nearly 600 acres of land were added to the island by lava flows from Kilauea volcano. This growth has not been without cost, however. Several towns have been destroyed by Kilauea: Kapoho (1960), Kalapana (1990), and Kaimu (1990). Today the remnants of these towns struggle to survive on the flanks of the world's most active volcano. In some aspects, these towns are all but abandoned except by a few. In 2018, Kilauea again destroyed much property on the northeast portion of Hawaii Island.

As previously mentioned, just 18 miles off Hawai'i's southeast coast is the undersea volcano known as Lo'ihi. Lo'ihi is an actively erupting seamount that lies approximately 3,178 feet below the surface of the ocean. If and when Lo'ihi breaks above the waves, it will likely join with Kilauea (which, in theory, will be much larger by that time) and become the sixth peak in what is now Hawai'i's largest island. Don't book your hotel room just yet though: it's a good 50,000 years or more in the making.

Lava Types

As you drive around the island you can't help but notice the various lava formations and lava fields that crisscross the island. If you pay especially close attention you're likely to observe there are two distinctly different types of lava flows. Around the Kona area, you'll quickly notice how clunky and jagged the lava is. In most of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, especially at the end of Chain of Craters Road, you'll notice the lava is very smooth, pillowy, and even ropy. These two unique flow types owe their origins to two distinctly different types of lava flows, Pahoehoe and A'a.

Pahoehoe Lava Flow

Pahoehoe

The word Pahoehoe (pronounced Pa-hoi-hoi) rolls off the tongue in the same fashion that it flows out of the volcano. It is smooth, and as the surface cools it forms ropy swirls and smooth hills. Pahoehoe flows slowly and steadily forward using bulbous toes to lead the way. As the toe (lobe) cools, it creates a thin layer. The hot lava continues to advance by breaking through the layer. The unique cracking sound of the cooled crust popping off often bewilders first-time visitors. The surface texture of pahoehoe flows can vary greatly. The viscous nature of pahoehoe makes it the perfect medium to create a variety of designs in the cooled lava.

'A'a lava flow

'A'a

The other type of lava is called 'A'a. 'A'a (pronounced "ah-ah") is the rough and tumble sister of pahoehoe. It rolls forth in clumps of broken lava called clinkers. The clinkers continue to pile up until the lava has cooled leaving a sharp, brittle pile of lava rock. It is difficult to find sure footing on the rubbly surface. The term 'a'a is actually said to have come from the ancient Hawaiians who would exclaim 'ah ah' as they walked over it with their bare feet. While the top of the flow may just look like a pile of rocks, underneath is a dense lava core which drives it onward. The crumbly surface clinkers are able to hitch a ride on top of the dense lava for a while, but eventually, they topple off the end and are rolled over. This process creates layers of fragments on the top and bottom of the advancing flow. It's almost like a glacier of fire.

Most of the lava that erupts in the islands begins its life as pahoehoe. Along with its journey, a variety of factors can make it change into 'a'a. The thickness of the lava and the resistance of the path it takes can make this change occur. The thicker the pahoehoe flow, the less resistance is required to turn it into 'a'a because it is moving so slowly. Conversely, the thinner and more free-flowing the pahoehoe flow, the harder it is to encounter the amount of resistance required to turn it into 'a'a. Once a pahoehoe flow has transitioned to 'a'a, there is no going back. Pahoehoe can turn into 'a'a, but 'a'a can never turn into pahoehoe.

Two other famous volcanic by-products are Pele's hair and tears. Both formed in fountaining eruptions, Pele's hair is thin strands of volcanic glass caught in the air during an eruption. Pele's tears are solid tear-shaped glass particles formed in the same way.

Subsidence & Erosion of the Hawaiian Islands

Though the Big Island of Hawai'i may seem incredibly large compared to its predecessors in the chain, in all likelihood it is not that much larger at all (historically speaking). Just across the 'Alenuihaha Channel sits the island of Maui and it's the greatest volcano, Haleakala. Geologists suspect that at one time Haleakala was not only joined to the West Maui Mountains, like today, but also was a single landmass combined with the islands of Lana'i, Moloka'i, and Kaho'olawe -- known as Maui Nui (literally, big Maui) (view map). The submergence of Maui Nui resulted in the volcanic body moved away from the Hawaiian hot spot. The lack of volcanic upbuilding combined with continued subsidence into the ocean floor eventually sank portions of the large island into the Pacific, providing us with the four separate islands we see today.

A similar fate awaits the Big Island in due time. As the hot spot "moves away" from the island (due to the Pacific Plate carrying the islands piggyback-style off to the north-west) the Big Island too will fall victim to subsidence and erosion. Eventually, the Big Island will likely find itself in a similar state to that of Maui Nui. It will become separate and smaller islands as the ocean encroaches on the flanks of each separate mountain. Such is the geologic circle of life beyond the Hawaiian hot spot.

For the next few thousand years, however, the Big Island will remain just that, big! It continues to represent an astounding 62% of the total land area of the Hawaiian Islands. And because Mauna Loa and Kilauea are currently still active and erupting volcanoes, the island of Hawai'i is still growing. The geologic future of the island is a work in progress.

If you're interested in even more 3D Hawaii Map images be sure to check out that page of our site. Below are also some of our favorite images from the good folks over at the Hawaii SOEST Mapping website run by the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

A larger version of the rendered map above (top) can be found here: Hawaiian Islands Map.